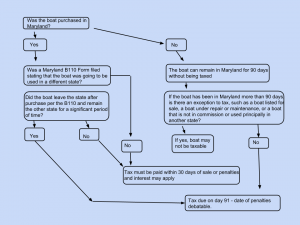

It has been some time since I discussed the basic issues with how Maryland taxes boats and yachts. The basics are that Maryland imposes a 5% tax on the purchase price or fair market value of any boat that is either purchased in Maryland or principally used in Maryland. There are a variety of exceptions to tax. A boat can be purchased in Maryland and taken out under affidavit for use in another jurisdiction. A boat can purchased elsewhere and brought in for up to 90 days without taxation. It can stay much longer without being taxed under certain special circumstances. Below is a rough graphic showing which boats are subject to tax and when. The most important initial consideration is whether the boat was purchased in Maryland.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Which State Can Claim Tax? (Or, where did the sale take place?)

What State can claim sales tax or Where did the purchase occur?

The state in which a purchase takes place (if any) is crucial to trying to determine who might have a claim for sales tax, and therefore on how much the claim may be. A good plan for boat tax should always start with being sure that the initial transfer takes place in a favorable location. This analysis is often complicated by the fact that the owner may live in one state, the seller in another, and boat and broker may be in a yet a third (or fourth) jurisdiction. So how does one go about answering this question? The crucial fact to determine is when and where the contract of sale is complete. For planning purposes, this is also a fact within the control of the buyer and seller.

In most states, laws concerning the sale of goods (including boats) are guided by the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), which is a model code that seeks to make laws on the sale of goods as uniform as possible in all 50 states. All fifty states have incorporated at least some parts of the UCC into their commercial code. While the UCC does not address or control sales tax, in many states it will define the “sale” and that will give a strong indication about where the sale takes place. In those states which have adopted the UCC’s definition of when a sale occurs, the buyer and seller have several ways in which they can dictate where the sale takes place, and thus where taxes must be paid.

Rule 1: The location called for in the contract controls.

The UCC provides “Title to goods passes from the seller to the buyer in any manner and on any conditions explicitly agreed on by the parties.” Md. Code Ann., Com. Law § 2-401. The most important thing in working out the logistics of anything having to do with a contract for the sale of goods — including where it takes place– is the language of the contract itself.

If the parties specify where and when the sale will take place, that usually determines where the boat is taxable. Obviously, there are limits to this, one can’t say the transaction takes place on the moon, if the boat and everyone associated with it is in New Jersey. Simply stating that a contract will be completed somewhere does not automatically make it so. However, if the seller is in Pennsylvania and the buyer is in Maryland, and the contract states that the sale is to be completed in Pennsylvania upon the seller sending the boat or title documents to the buyer, then the sale took place in Pennsylvania. Likewise, if the contract says that the sale will be complete upon the buyer receiving the boat or title documents in Maryland, then the sale will be deemed to have occurred in Maryland. If the boat is moved to Delaware for the closing, the sale takes place in Delaware.

Rule 2: If there isn’t an express agreement, the sale happens where the boat is delivered.

“Unless otherwise explicitly agreed title passes to the buyer at the time and place at which the seller completes his performance with reference to the physical delivery of the goods, despite any reservation of a security interest and even though a document of title is to be delivered at a different time or place.” Md. Code Ann., Com. Law § 2-401.

If the contract does not specify where the sale is going to happen, then the location of the sale is generally determined by whether the location where the boat is delivered, nothwithstanding the delivery of title documents elsewhere. If the seller is responsible for delivery, then the sale occurs wherever the boat is delivered to the buyer. If the buyer is responsible for delivery, then the sale happens where the boat is transferred to the buyer or to a shipping company at the direction of the buyer. So, if the boat is built in North Carolina for a buyer located in Maryland, and the buyer goes to North Carolina to get the boat — the sale takes place in North Carolina. If the contract calls for the dealer to deliver the boat to Maryland, however — the sale probably takes place in Maryland.

Rule 3: If the boat is staying put, the sale happens where the last key paper is delivered.

Unless otherwise explicitly agreed where delivery is to be made without moving the goods, (a) If the seller is to deliver a tangible document of title, title passes at the time when and the place where he delivers such documents and if the seller is to deliver an electronic document of title, title passes when the seller delivers the document; or (b) If the goods are at the time of contracting already identified and no documents of title are to be delivered, title passes at the time and place of contracting. Md. Code Ann., Com. Law § 2-401 (West)

If the boat is not being moved as part of the purchase contract, then the sale will happen when the seller gives the buyer the title documents — which generally does not happen until after payment is made (there are exceptions!). The location is easy to determine if the seller and buyer are in the same location, and the buyer physically hands the seller the title documents. If the seller is either mailing or electronically transferring the title documents, the law is a bit less clear. The parties can still stipulate in the contract whether the sale is complete upon sending or receiving of the title documents, and the contract will control the location. If the parties have not stipulated when the sale is complete, then it is like the sale happens where the buyer receives the contract, but Maryland has not addressed that directly.

It is also noteworthy that a Coast Guard Document (and the Bill of Sale that must be filed to transfer a documented vessel) are not considered to be title documents, at least by most Courts. This means that a boat that has a state title may be treated differently from a boat that is Coast Guard Documented.

Final Thoughts

For most boats, the State of transfer will be plain and the exact timing of the sale will not matter too much. For a high value boat, however, selecting the State of transfer may be an easy way to avoid or defer a payment that can reach hundreds of thousands of dollars. To be sure that things are done right, the contract should call for a specific state and for the sale to take place only at a specified moment, and the contract language should reflect the real-world actions of the parties. If the contract does not specify, then care must be taken to have the boat (or the documents) change hands in the correct jurisdiction. On a final note — I have never done a formal poll, but I imagine that most boat tax administrators believe that the boat’s location at the time of sale is the most important (or only!) fact concerning taxability. For this reason, notwithstanding what the law says, I always pay close attention to where the boat is at time of closing. Good luck, and feel free to shoot us an email if you have a question.

Boat Tax New Jersey – 2016 Update

Boat Tax New Jersey 2016

Until recently, New Jersey had been among the toughest states in the Mid-Atlantic as far as boat tax. One client kept his boat in Delaware, but took a weekend trip to New Jersey with his local yacht club. While there, his information was reported to tax authorities — and suddenly his weekend in the state came with a five figure tax bill. He was on the hook because New Jersey took the position that if a resident brought a boat in even for a single day, that boat was subject to the use tax.

The State, however, has recently passed three changes to the tax. These taxes primarily impact more expensive boats and boats that are not used in exclusively in New Jersey. First and foremost, a cap of $20,000 has been placed on the total amount of tax that can be collected and taxes on boats have been cut to 3.5 percent: “Notwithstanding the provisions of P.L.1966, c. 30 (C.54:32B-1 et seq.) to the contrary, receipts from the sale of a boat or other vessel are exempt to the extent of 50 percent of the tax imposed under section 3 of the “Sales and Use Tax Act,” P.L.1966, c. 30 (C.54:32B-3) and the maximum amount of tax imposed and collected on the sale or use of a boat or other vessel shall not exceed $20,000.” N.J. Stat. Ann. § 54:32B-4.2.

The second important change has been to create a window of time in which a resident can use their boat in New Jersey without paying tax for the use. Per the new rules, a resident can use the boat for not more than 30 days in a calendar year without tax so long as it is properly registered and numbered in another state and is not being used for business in New Jersey.

“Notwithstanding the provisions of P.L.1966, c. 30 (C.54:32B-1 et seq.) to the contrary, the use within this State of a boat or other vessel for temporary periods, not totaling more than 30 calendar days in a calendar year, shall not be subject to the compensating use tax imposed by section 6 of P.L.1966, c. 30 (C.54:32B-6), provided that: (1) the boat or other vessel is legally operated by the resident purchaser and meets all current requirements pursuant to applicable federal law or pursuant to a federally-approved numbering system for boats and vessels adopted by another state, and (2) the resident purchaser is not engaged in or carrying on in this State any employment, trade, business, or profession in which the boat or vessel will be used in this State.” N.J. Stat. Ann. § 54:32B-6.1 (West)

In short, if you have received an assessment from the State of New Jersey, then there are two immediate questions to ask. Is the boat owned by a New Jersey resident? Of if it is a corporation, are the beneficial owners New Jersey residents? Second, if not, is the boat privately owned and not being used in a commerce or trade? If there is no resident and the boat is privately used, use tax should not be imposed for a temporary use of New Jersey waters.

Fair winds.

Dirk Schwenk

2005 Court of Appeals Decisions

Dirk Schwenk’s note, January 2010: Boat owners should be aware that the statute was changed after this decision and no longer requires that a boat be purchased with the intent that it be used in Maryland waters. There remain significant other defenses to an assessment for vessel tax.

_____________________________________________

On March 14, 2005, Maryland’s highest court, the Court of Appeals, spoke for the first time on the interpretation of Maryland’s vessel excise tax. In Kushell v. DNR, a case briefed and argued by J. Dirk Schwenk. The Court held that the Department of Natural Resources could not tax all federally documented vessels. For decades, the DNR had taken the position that it could tax any boat that was principally used in Maryland. Mr. Kushell admitted to having his boat in Maryland, but argued that he did not purchase the boat with the intent that it be principally used in this state, since he had used it in California for nearly a decade before entering Maryland waters. Kushell argued that he could only be taxed if he had: “possession within the State of a vessel purchased outside the State to be used principally in the State” under the statute.

This argument was repeatedly rejected, including by the Office of Administrative Hearings (the first level of the case); the Secretary of the DNR (the second level of appeal); and the Circuit Court for Anne Arundel County (the third level of appeal). The Court of Appeals, however, unanimously agreed with Mr. Kushell (and Mr. Schwenk) and held that the plain language of the statute required that, to be taxable, a federally documented boat must be purchased with the specific intent that it be principally used in Maryland.

Because of the way that boat tax is structured, this should also mean that a boat purchased and registered in another state is not taxable, so long as the numbering system of the other state is maintained. On the same day, the Court issued a second decision concerning the boat tax. This appeal was not handled by Baylaw, LLC, and its result went against the vessel owner. In Schwarz v. DNR, the vessel owner purchased the boat in Maryland, but did not remove it within 30 days as the DNR requires in order to avoid tax. The vessel owner argued that he kept the boat in Maryland for a longer period because the boat required significant warranty repairs.

Ultimately, the vessel owner invested nearly $35,000 in after-market stabilizers to address a significant stability issue, then took the boat South to Florida. During the first appeal, the Office of Administrative Hearings held that Mr. Schwarz did not meet the repair exception to the tax because the boat had not been “held for maintenance or repair” for periods of greater than 30 days, and it was therefore simply being used in Maryland waters. In the Circuit Court, the judge held that there was no exception at all to the tax for a boat that was purchased in Maryland, and so the “maintenance and repair” exception did not apply. The Court of Appeals clearly struggled with whether the Circuit Court was correct, but in a split decision analyzed the case on the basis of the maintenance and repair issues. In so doing, the Maryland’s boat dealers and brokers narrowly avoided a decision that could have crippled the industry, since every boat purchased or sold in Maryland would have been taxed, irrespective of where the boat was to be used.

In dissent, Judge Wilner stated: “If the Circuit Court’s reading of the statute is correct [that there is no exception to the tax for boats that are purchased in Maryland], but may cause some economic hardship to the boating industry in Maryland, the industry can ask the General Assembly, which is now in session and will remain in session for another month, to reconsider the tax statute and create the exemption that is not presently there. That is the normal way, and a perfectly effective way, in which a statutory construction decision by this Court can be reviewed by the Legislature. If the General Assembly believes that the kind of exemption created by the Department of Natural Resources should exist, it can easily and quickly place it into the law. To acknowledge but then fail to address the issue will, because of the lingering uncertainty, create more of a hardship for the boating industry than a clear decision which, unfavorable to the industry, can easily be corrected by the legislature.”

And so, boat dealers and brokers were that close to losing the 30 day exemption to the boat tax. What the DNR will do next remains to be seen. The Court’s decision can be found at Schwarz v. DNR. Dirk Schwenk’s Note, December 2009 — The DNR and legislature did modify the statute to expressly provide for a 30 day window in which to take a boat purchased in Maryland out of the state. There is also now a 90 day window in which a boat purchased elsewhere can be brought into Maryland and cruised.

As always, boat tax issues are entirely tied up in the peculiar facts of the situation, and this page must be viewed as general information and not specific advice. The intent of a purchaser is particularly subject to inference, and should be presented in the best possible light, if one is to achieve success on this point. There are no cases addressing the fine line indicating when a boat is purchased with the intent that it be principally used in Maryland, so this area is ripe for both powerful advocacy and grave misstep. If proceeding without representation, great caution is advised.