Eds. Note: This article appeared in The Law Clerk, a publication of the Maryland State Bar Association, in May, 2005. Its author is Michael J. Jacobs, an attorney from Easton, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, and the opinions expressed in this article are his. At Baylaw, LLC, we believe that many of the concerns with the process noted by Mr. Jacobs can be minimized with careful advanced planning, and by knowing when to recommend settlement as an alternative to litigation. We do not recommend that anyone testify on behalf of themselves in boat tax cases — particularly attorneys with boats — unless they are represented by knowledgeable counsel.

Casenote.DNR.cases.5.11.05 – MSBA 2004/05 Law Clerk

Practice Tip

Sailing into the twilight zone of the Maryland vessel excise tax? You’ll need more than running lights.

Schwartz v. DNR, Court of Appeals No. 94, September Term 2004, March 14, 2005 (Judge Raker with dissent by Judge Wilner).

Kushell v. DNR, Court of Appeals No. 96, September Term 2004, March 14, 2005 (Judge Raker).

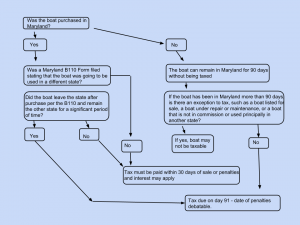

A client walks in the door, fuming at the assessment of the five percent Maryland vessel excise tax on his or her vessel pursuant to Natural Resources (DNR) Art. §§ 8-716 et seq. The vessel was purchased in Maryland to be moved to permanent moorings at the client’s home in another state. As such, it was not supposed to be subject to that tax.

However, as often occurs, the vessel had a number of serious operational problems, serious enough to prevent it from leaving Maryland until repaired. Your client expected the dealer to remedy the problems. And the dealer did so. But it took some time to get the work done.

While the work was in progress, on 3 or 4 occasions, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) made brief observations of the vessel while it was moored in Maryland waters undergoing repairs. Those observations took about 10 to 12 minutes in toto. That was, in fact, the total duration of the observations in theSchwartz case.

Those observations will have been made by persons who likely have no meaningful expertise about the vessel involved. The DNR observer likely did not try to determine why the vessel was moored there.

Based on those events, the DNR determined that the vessel excise tax was due because those passing glimpses indicated that Maryland must be the state of principal use for the vessel, or more realistically, the DNR wished to force your client to prove otherwise. Accordingly, the DNR issued a notice of assessment imposing the tax with interest and penalties.

From that point on, immediately upon the issuance of that notice, there has been a lien on the vessel for the tax, interest, and penalties, a lien which has ‘the full force and effect of a lien of judgment.’ NR Art. § 8-716.1(f)(2). Was your client planning to refinance the vessel? Make sure that he or she discloses that judgment lien.

Did you believe that pursuant to fundamental due process requirements articulated by the Supreme Court in Sniadach v. Family Finance Corp., 395 U.S. 337, 89 S.Ct. 1820, 23 L.Ed. 2d 349 (1969), and by the Court of Appeals in Barry Properties, Inc. v. The Fick Brothers Roofing Company, 277 Md. 15, 353 A.2d 222 (1976), there could be no such judgment lien without notice and the opportunity for a hearing prior toimposition of such a lien? Wrong. In the three plus decades since Sniadach, the ‘ripple effect’ of the multitude of cases flowing from Sniadach and its progeny has yet to reach this Maryland law.

But wait. You see that you should be able to help the client by denying liability within 30 days of the issuance of the notice and requesting a hearing before an administrative law judge (ALJ). You note that if the vessel was held for maintenance or repair for 30 consecutive days or more, that time cannot be included in the calculation to determine the principal state of use. NR Art. §§ 8-716(a)(3) & 8-701(n). And that, of course, was the only reason that your client’s vessel was even in Maryland waters at the time the DNR wandered by. Further, you see the obvious bases for solid constitutional challenges to various aspects of that tax.

So this should be fairly cut and dried process. Want to bet? Once you start the process of contesting liability for that tax, you have entered the twilight zone. You are going to need more than running lights to find your way through the process. That process may well take up to three years before you reach any reasoned resolution, if, in fact, you ever do reach a reasoned resolution. In the meantime, the judgment lien for the tax will remain in effect, with interest accruing.

How does the process work? With the filing of the appeal, an ALJ will, in due course, conduct a hearing pursuant to the Administrative Procedures Act, State Government Art. §§ 10-201 et seq. The DNR will establish conclusively that the vessel was in Maryland waters for the several minutes it took to make its passing observations of the vessel. It will call as its experts, persons who will likely have little experience with or knowledge of such vessels.

You should be aware that to the extent that the ALJ bases his or her findings on the testimony of those DNR experts, at the judicial review stage, the qualifications of those experts will be difficult to challenge. This is so because when you do reach the stage of judicial review, findings based in part on the DNR experts will, under Maryland law, be entitled to great deference.

Will your client’s case depend in part on witnesses you need to subpoena from out of state? Forget it. No subpoena is available for such witnesses. And even if you submit their affidavits, notwithstanding that the setting is an administrative hearing with relaxed rules of evidence, the DNR will object due to the inability to cross-examine the witness. The ALJ can be expected, in turn, to reject or ignore that affidavit evidence. So your best hope is that your witnesses are in Maryland, or at least willing to cooperate in providing needed testimony.

You should be aware that it is your client’s burden to prove in the administrative process, that he or she is not liable for the tax. As a practical matter, the DNR typically only has to prove that the vessel was in Maryland waters in order to get the tax affirmed through the administrative levels. Your client, in turn, having had a judgment lien placed on his or her vessel without the opportunity for a hearing, will be required by the DNR and the ALJ that the tax is not, in fact, due. Unless you can prove that, the lien will remain in effect.

You will likely need to review the prior administrative interpretations of the issues involved in your client’s challenge to the tax. However, you will find that there is no index or reporting system which permits you to accomplish that short of trying to extract that information from the Office of Administrative Hearings (‘OAH’) in Towson. Those efforts should be premised in part, on a Public Information Act (‘PIA’) request, so as to establish your legal entitlement to such information.

But you still may encounter resistance from OAH to your accessing the public records consisting of prior ALJ decisions. A better course will likely be to identify a colleague familiar with the decisions, to see if you can get an assist, to avoid a trip to the OAH in Towson.

Even if you do access the prior ALJ decisions on the issues in your case, you will not get access to the interpretations of the Secretary of DNR on the multitude of ALJ proposed decisions. Those rulings may well evidence the policies and practices of the DNR, considerations which may be important to the case. A PIA request to the DNR may help with that.

How about the case law, the reported decisions illuminating the judicial interpretations of the tax and its procedures. There are few reported decisions. The two referenced cases are amongst those that do address the tax.

The underlying reason for the lack of case law is cost-effectiveness concerns in reaching that stage of the process. The length and lopsided nature of the procedures needed to even reach the courts, weighed against payment of the tax, create significant obstacles to any meaningful judicial involvement in the process. That tends to explain why the ripple effect ofSniadach has yet to reach these statutes.

You likely plan to raise the obvious procedural and constitutional challenges pertinent to these lopsided proceedings. To do that, you must keep in mind the jurisdictional requirement that your client must first exhaust his or her administrative remedies [see, e.g., Blumberg v. Prince Georges County, 288 Md. 275, 418 A.2d 1155 (1980)]. As futile as the effort may seem, those challenges need to be raised early in the administrative processes.

A failure to do so may leave you with the need to ask for a remand once you finally do reach the courts. Maryland Insurance Commissioner v. Equitable Life Assurance, 339 Md. 596, 664 A.2d 862, 872-877 (1995). You should try to avoid that risk.

In order to exhaust administrative remedies, once the ALJ issues a proposed decision affirming the tax assessment and the procedures involved, in an abundance of caution, your client should submit exceptions to the proposed decision to the Secretary of the DNR prior to secretarial action to approve the proposed decision.

You correctly believe the prospects are nonexistent that the Secretary will say that no tax is due. But you still need to take that further time-protracted step in order to finally reach the stage of judicial review.

In the judicial review process, the standard of review is set forth in State Government Art. § 10-222(h). That standard is discussed, inter alia, in the Kushell andSchwartz decisions.

The decision in Kushell addressees a narrow issue. There, the vessel owner had purchased the vessel outside Maryland for use outside of Maryland. He had actually used the vessel for some time in California before moving to Maryland, bringing the vessel with him.

In Kushell, the Court rejected the DNR 12-minute rule of tax liability (see, e.g., Schwartz, supra) on the basis that the statute did not permit such an assessment where the vessel was purchased outside of Maryland with the intent to use it in another state. Accordingly, after three years and considerable legal effort and, presumably, expense, Mr. Kushell’s vessel was finally freed of the judgment lien but with no apparent relief to the vessel owner who had been subjected to the DNR proceedings.

The Kushell briefs did raise some of the constitutional challenges apparent in this lopsided process. However, given the focus of the Court of Appeals on the inapplicability of the tax to the Kushell vessel, those issues were left for another day.

Dirk Schwenk from Annapolis was the successful attorney for Mr. Kushell. Dirk notes that the implications of the Kushelldecision indicate that the following situations should be exempt from the tax: (EDS. NOTE: It is our understanding that legislation is to be introduced in the 2006 legislative session that will effect the holdings of Kushell v. DNR, by changing the key language. DO NOT rely on this concerning taxability of a vessel in the future)

1. Federally documented vessels purchased elsewhere where the owner did not plan at the time of the purchase, to bring the vessel to Maryland.

2. State numbered vessels purchased elsewhere and properly numbered in that other state, where the owner did not intend at the time of the purchase, to bring the vessel to Maryland.

Examples for both categories would include out-of-state residents relocating to or visiting Maryland, so long as the vessel was initially purchased for use in another state before it was later relocated to Maryland.

The decision in Schwartz is of more interest, for both the issues it did address as well as the issues it sidesteps. TheSchwartz decision was handled by Matthew Egeli, also of Annapolis. It has marked parallels to the hypothetical case posed here. In Schwartz, the Court was considering the more typical history of vessel use and the tax assessment process.

The vessel had been purchased in Maryland for relocation and use in another state. Accordingly, following DNR regulations, the purchaser had submitted to the DNR, a completed DNR form B-110. The procedure gives rise to a procedural exemption so that the dealer is not required to collect the excise tax.

However, after the sale, it became apparent that significant operational and stability concerns required that the vessel remain in Maryland for some time. Accordingly, the vessel became subject to what might be called the DNR 12-minute rule of tax liability. A three-year odyssey of administrative and judicial proceedings ensued, with the predictable administrative determinations taking up much of that time.

Somewhat atypically, the venue considerations allowed the judicial challenge to be filed in the Circuit Court for Queen Anne’s County. That Court had found by a careful an obviously careful analysis, that the law did not permit the DNR form B-110 exemption, that the dealer should have been required to collect the excise tax for a vessel sold in Maryland.

This was not an issue which had been raised by any of the parties in the earlier administrative proceedings. On that point, you need to read the circuit court decision in the Schwartz case in order to understand that analysis. The Court of Appeals’ opinion does not provide any detail on the analysis below by the Circuit Court.

Unexplained in Schwartz is the point that the issue decided by the circuit court had never been raised in the administrative proceedings below, but the issue of exhaustion of administrative remedies was not addressed. Maryland Insurance Commissioner v. Equitable Life Assurance, supra. Unexplained in the decision of the Court of Appeals, was why that requirement was not addressed.

As with Kushell, the Court of Appeals granted by-pass certiorari. That grant ofcertiorari in the Schwartz case was apparently to consider the striking down of the long-standing DNR form B-110 exemption by the Circuit Court. However, as noted in a forceful dissent by Judge Wilner, the decision sidestepped the lack of a DNR form B-110 exemption. Instead, it then went through a painstaking analysis of the administrative record to affirm the imposition of the tax.

What is really going on in these cases? Maryland marinas in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries are filled with literally acres of very expensive vessels. These vessels feed an important industry group involved in the sale of those vessels for use in Maryland and elsewhere. The DNR form B-110 exemption provides some administrative support for that industry group.

Maryland also has a viable and important vessel service and repair industry. That industry group services vessels from outside the state which certainly do not wish to be assessed an excise tax simply because they chose to use Maryland services and facilities. And certainly, the businesses providing repair and related services for vessels generate business and tax revenues for the state.

It is this industry group that would seem to be victimized by the DNR 12-minute rule of tax liability. Fortunately for that group, it would appear that the out-of-state prospective users of that service industry are not aware that the price of using those Maryland service facilities may, by reason of the DNR 12-minute rule, include the excise tax.

The DNR has an advisory group which seeks, in part, to strike a balance between keeping those industry groups viable while still permitting the DNR to use its 12-minute rule, to run roughshod over fundamental due process and related concerns.

In this straining economy replete with state budget problems, it is would seem to be apparent that the courts will have a strong predisposition to upholding the tax wherever possible and with it, the DNR 12-minute rule.

Witness the dissent in the Kushelldecision. As Judge Wilner notes, the issue of cert-related concern was the exemption which would have been struck down by the circuit court ruling. If the DNR form B-110 exemption were invalid, it is foreseeable that vessel sales and the related servicing of those vessels would be lost to Maryland.

In his dissent, Judge Wilner states that if there is no exemption, then without regard to the intended ultimate use of the vessel, the dealers for all vessel sales in Maryland should collect the tax. He notes, as well, that there may be economic hardship for the boating industry in Maryland, that legislative action may ensue.

The majority opinion sidesteps consideration of that prospective loss of the DNR form B-110 exemption, to hold that under the facts in that particular record, the DNR had properly assessed the tax. In doing so, it avoids the risk of hardship to the involved industries and the risks inherent in the legislative process. On that point, it would seem to be obvious that no vessel owner’s challenge to the assessment of the tax would be likely to take issue with the DNR form B-110 exemption.

Where does that leave you and your client in the client’s prospective challenge to the assessment? It suggests a long and uncertain voyage through waters filled with unrevealed hazards in the form of unstated agendas and concerns not apparent on the surface of the statute and the regulations. You’ll need more than running lights to detect those submerged obstructions. Make sure that your client understands the course to be plotted.